- Home

- Scotland's changing climate

- Urban Housing in Scotland

- Maintenance

- Ventilation

- Airtightness

- Insulation

- Lofts - insulation at ceiling level

- Lofts - insulation at rafter level

- Cavity wall insulation

- Solid Walls: Internal vs External Insulation

- Internal Solid Wall Insulation (IWI)

- External Solid Wall Insulation (EWI)

- Timber frame retrofit

- Windows and doors

- Openings in 'historical' buildings

- Openings in 'non-historical' buildings

- Ground floors

- Suspended floors

- Suspended floors - from below

- Suspended floors - from above

- Solid floors

- Insulation materials

- Building science

- Space heating

- Solar energy

- Product Selector

Comfort

It should be clear from the previous section that temperature and heat loss, air flow and moisture are all interrelated; change one, and you alter the other two, with knock-on effects on the building and the people in it. Until about ten years ago, most discourse on retrofit was restricted to heat loss and insulation. In the last ten years, most people in the industry have become more aware of the need to look at air movement, but in the future, we need to broaden our area of focus again to include moisture and ventilation, which connects to all three.

It is important to discuss comfort because, with the focus so heavily on the sorts of technical and physical changes needed to buildings, it is easy to forget that it is not really buildings we are trying to keep warm – it is people.

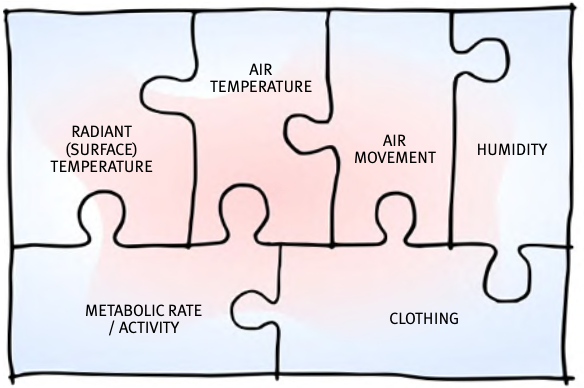

Comfort is a major topic of debate, albeit mainly within the building services sector. There is an International Standard – ISO 7730 – which describes the general conditions which need to be met in buildings to optimise comfort levels for most people. There are broadly six components of what constitutes comfort, shown in the diagram to the right.

Having lived for many years with central heating, most people in Scotland would consider air temperature the most important, if not the only, parameter of comfort. After all, it is usually the only thing we get to control on our thermostats. However, in fact, the radiant surface temperatures surrounding us are the most important. See the section on heating for more on this, but the problem for most is that we do not have a way of controlling this in most heating systems. It is also worth noting that humans tend to feel more comfortable with warm feet and cool heads, so any system of creating comfort should strive to provide those conditions.

In the last 15 years, another approach has developed, recognising that everyone has different ideas of comfort. It is called the ‘adaptive comfort’ approach. Whilst adaptive comfort recognises some basic parameters of comfort, it acknowledges that some people can operate quite happily outside the ‘normal’ confines described in the more prescriptive standard. An adaptive comfort approach recognises that older, infirm and sedentary people and those from warmer countries tend to need higher temperatures. Younger, more active people will be more likely to tolerate lower temperatures. This also tends to be true for people from colder climates or otherwise used to being in cooler conditions. Adaptive comfort also acknowledges that even for the same person, boundaries of what is comfortable alter across seasons – we are more tolerant of higher temperatures indoors when it is warmer outside and vice versa.

The critical outcome of adaptive comfort is the need to design for personal control. People who can exert control over their immediate surroundings (opening windows, operating fans, adjusting local heating) will tolerate much more variety in their surroundings than those without such control and are obliged to ‘put up with’ standardised, often remotely controlled conditions. This is known as the ‘forgiveness factor’ and takes the typically technologically driven world of building services deep into the territory of psychology and behavioural studies. In terms of designing buildings, the adaptive comfort model suggests basic parameters and then concentrates on creating opportunities for individuals to control their environment. This is why the subject of controls is an important aspect of this guidance.