- Home

- Scotland's changing climate

- Urban Housing in Scotland

- Maintenance

- Ventilation

- Airtightness

- Insulation

- Lofts - insulation at ceiling level

- Lofts - insulation at rafter level

- Cavity wall insulation

- Solid Walls: Internal vs External Insulation

- Internal Solid Wall Insulation (IWI)

- External Solid Wall Insulation (EWI)

- Timber frame retrofit

- Windows and doors

- Openings in 'historical' buildings

- Openings in 'non-historical' buildings

- Ground floors

- Suspended floors

- Suspended floors - from below

- Suspended floors - from above

- Solid floors

- Insulation materials

- Building science

- Space heating

- Solar energy

- Product Selector

The Inadequacy of Most Modern Ventilation Systems

All ventilation systems in buildings have three components in common, whether designed or not:

1. some form of extract system which removes stale air

2. some form of intake which allows fresh air into the building to replenish that lost

3. and some arrangement of transfer of air between these points.

Several recent studies in Scotland and the UK have shown that, too often, the actual performance of the various ventilation strategies employed needs to be improved compared to the requirements of the Technical Standards. The reasons for the poor performance of ventilation systems are complex, interrelated and often quite nuanced. Still, some central issues are noted below, relating to the three main components.

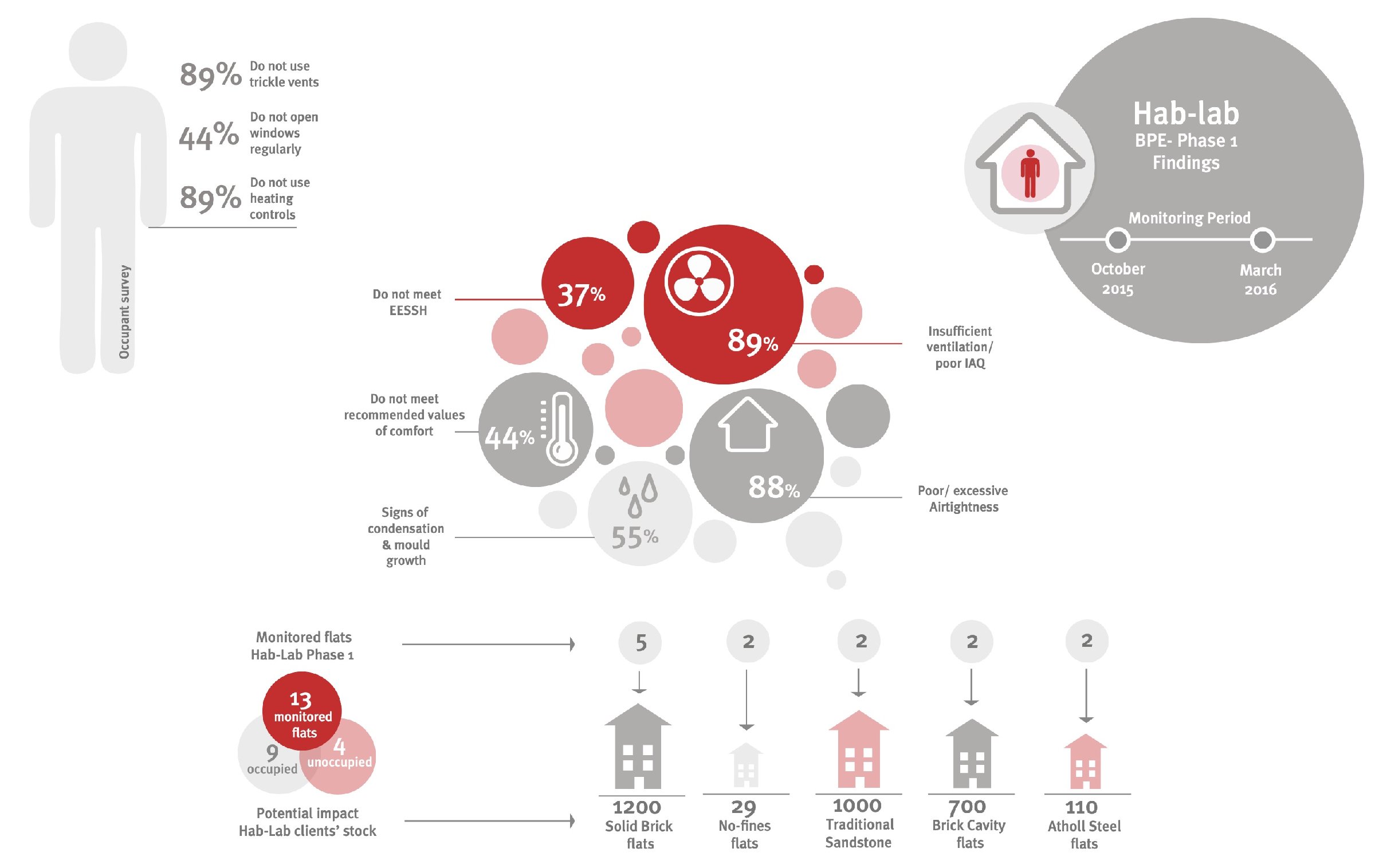

This infographic shows some of the early findings of the ‘Hab-Lab’ project, perhaps

the most significant of which was the widespread inadequacy of most existing • ventilation systems

Some extract fans are too small to work well and can be too noisy leading many not to be used, or switched off completely

Extract fans placed near trickle vents will short circuit, meaning the rest of the room, and other rooms, can be under-ventilated

Extract Routes / Equipment are often inadequate:

- passive stack ductwork does not exert the requisite draw

- other natural stack or cross-ventilation routes are compromised by fluctuating weather conditions

- extract fans are incorrectly sized

- fans are connected to ductwork, which increases resistance without adjustment made.

- extract fans are noisy and turned off, disconnected or simply not used

- fans are broken and have not been replaced

- filters are clogged with dirt or grease (e.g. in kitchens) and no longer extract effectively

Inlets are often inadequate:

- located too close to extract routes, creating short circuits which leave other areas under-ventilated

- located in wet rooms, thereby creating a short circuit and other rooms under-ventilated

- inlets are left closed (occupants either don’t know about them or have left them closed deliberately)

- inlets are under-sized

- inlets are partially or fully blocked by dirt and debris.

Finally, anticipated transfer routes often become blocked:

- partition doors are kept closed, do not have the requisite undercut, or are blocked by carpets

- transfer grilles are blocked, sometimes intentionally, e.g. where related to contradictory fire regulations

- inlets are compromised by too many adjacent obstacles, such as net curtains, full curtains, blinds, etc.

In some properties, the high levels of air leakage can mean that fans tend to draw incoming air from the gaps in the house rather than the designated inlets, meaning the system doesn’t work as intended. Ventilation systems that would ordinarily function correctly can also be overloaded by occupant behaviour such as overcrowding of rooms (particularly bedrooms), drying of washing indoors, venting tumble driers into a room rather than outside and what might be called ‘excessive’ or at least unanticipated use of showers, baths, kettles, cooking and so on.

Many of the above ‘real-life’ issues have been encountered in investigations and can lead to situations where levels of ventilation within a property are far from expected. Sometimes, this is deliberate – many people close off the various ventilation inlets when it is cold to keep the home warmer – while at other times, it is unintended. Either way, while properties may be warmer, all the moisture and pollutants that were supposed to be exhausted build up inside the home.

The most obvious problems occur when moisture or humidity levels increase beyond the point at which the air can contain them. At this point, water condenses out of the air, usually at the coldest nearby surface, leading to condensation and, if circumstances are right, to mould. While problems with mould are unwelcome, they also tend to be easily seen and, therefore, more readily dealt with. The build-up of chemicals off-gassed from the plethora of synthetic furniture and fittings in most modern homes is equally undesirable. The problem here is that occupants do not easily sense the build-up of these chemicals; they cannot be seen, and while people often open windows to cool down, research shows that they are less likely to open windows to reduce ‘stuffiness’. The harmful effects can go unnoticed, and the results can act upon occupants cumulatively for years.

Ventilation must be considered an integral part of any retrofit project, even if it is simply a case of checking the existing system to ensure that it is operating effectively. In the next section, we provide practical recommendations for what to do in two retrofit scenarios.

Existing Extract Fans with Openable Windows / Trickle Vents

These systems are by far the most common in Scotland. Working correctly, the systems can effectively keep both odour and moisture levels down to acceptable levels at low capital and running costs. As discussed above, many systems must operate adequately; many suffer from being too noisy, and heat is not recovered.

This kitchen trickle vent was completely blocked by debris mixed with grease

Many planned 10mm clear undercuts are compromised by later carpet installations

The trickle vent in this bedroom window was kept closed, as was the door, meaning there was not enough fresh air to clear the moisture in the air, leading to condensation and mould on the coldest available surface – the window frame and reveals.

This occupant cannot reach her trickle vent, which is not readily controllable. It is open, but the net curtains reduce airflow to the room.