- Home

- Scotland's changing climate

- Urban Housing in Scotland

- Maintenance

- Ventilation

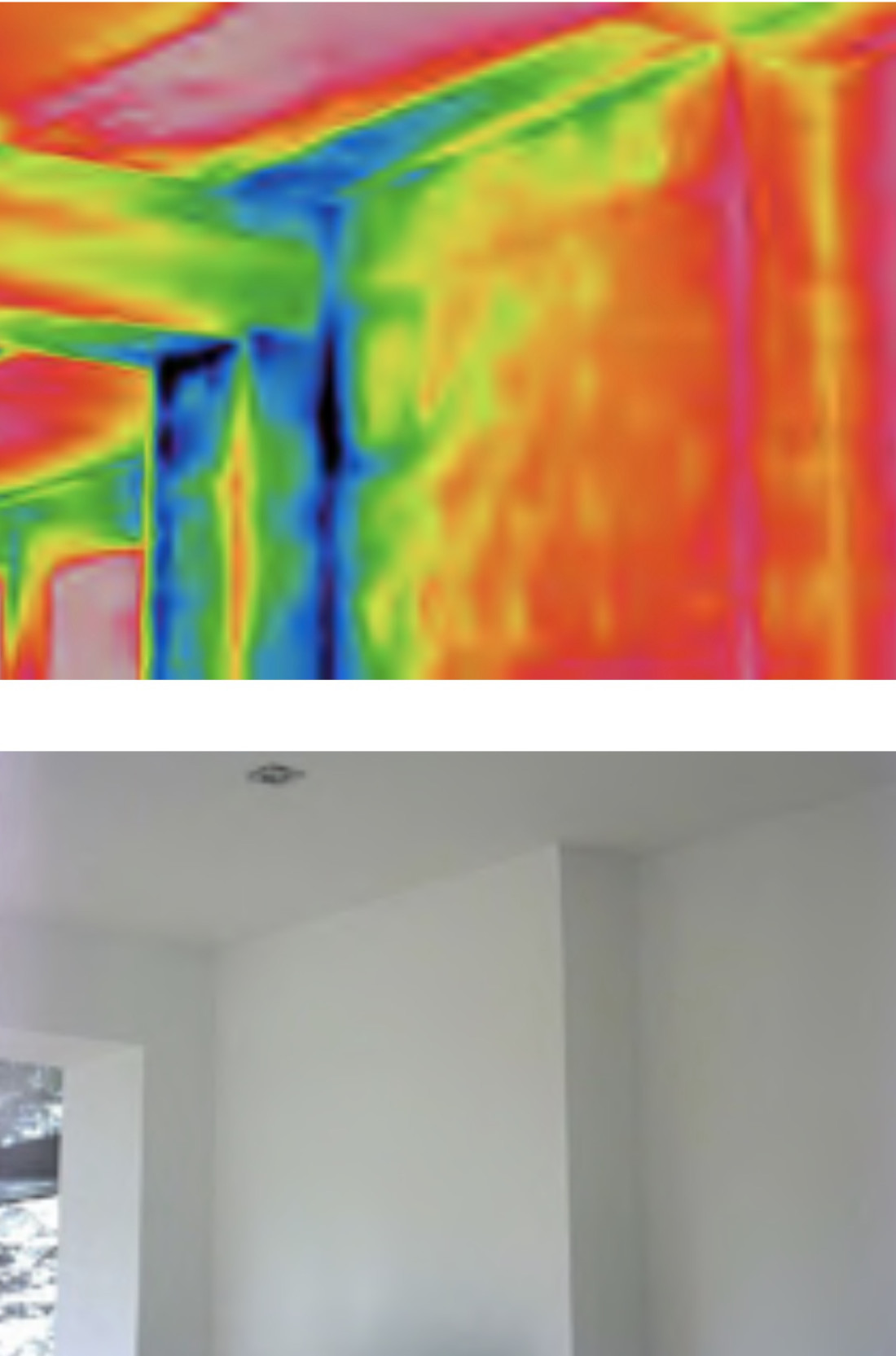

- Airtightness

- Insulation

- Lofts - insulation at ceiling level

- Lofts - insulation at rafter level

- Cavity wall insulation

- Solid Walls: Internal vs External Insulation

- Internal Solid Wall Insulation (IWI)

- External Solid Wall Insulation (EWI)

- Timber frame retrofit

- Windows and doors

- Openings in 'historical' buildings

- Openings in 'non-historical' buildings

- Ground floors

- Suspended floors

- Suspended floors - from below

- Suspended floors - from above

- Solid floors

- Insulation materials

- Building science

- Space heating

- Solar energy

- Product Selector